The Bhagavad Gita is an ancient Hindu text. It is a small part of the much greater volume called the Maha Bhartava, which focuses on the Pandava family and the battle at Kurukshestra, in the early days of India. In my mind, this is the warrior’s guide to living and to recovery.

PTSD is a devastating condition resulting from over-stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system. This is the part of our physiology associated with ‘fight, flight or freeze.’ It is an extremely useful reflex for surviving dangerous situations. It takes the energy and focus, and applies them to awareness, speed and other attributers that can keep us alive in an emergency. PTSD – post traumatic stress disorder, has to do with the displacement of this anxiety in time. That is, we respond as we need to, often with level heads and apparent calm, in a crisis. Then when the crisis is over, we do the freaking out we weren’t able to do when our lives were threatened. If the traumatic situation was powerful enough, or repeated enough, or lasted over a long period of time, then we can be triggered to experience ‘flashbacks’ – or situations when the mind is taken back by a trigger – say a smell, or a sound like gunfire or fireworks, and we find ourselves reliving the stressful situation.

Lots of soldiers, first responders and victims of abuse suffer from PTSD.

The Bhagavad Gita, being a warrior’s tale, I believe, gives us insight into why we do heroic things, and how we can understand a bit about what PTSD is, and how to put it in context.

As a sufferer of PTSD, myself, I have found yoga to be invaluable in helping me cope, both with stressful situations, and how to understand PTSD. This is not to say that sometimes there are not breakthrough symptoms. Sometimes life is just overwhelming. Sometimes our practice takes a back burner to the expectations life has of us. But, I believe my quality of life is much much much better due to my yoga practice and yoga philosophy.

The story begins on the eve of the battle.

Krishna is the embodiment of God on earth. He was a real, historical character. There was a real war. This exchange may be real or mythological, or symbolic. I will look at it as symbolic.

Arjuna is the warrior of the Pandava family. He is a very skilled warrior. Prior to the start of the story, the Pandavas have been wronged for many years. They lost their rightful leadership of the country, and have been banished to the jungle. They have tried to solve the problems through diplomacy, and many other means, and have given up all their status and wealth trying to avoid conflict. The Kauravas, the family who has stolen power from the Pandavas, are now abusing the people, and must be stopped. This established that this is a righteous and unavoidable war. Like many of the situations we find ourselves in, we did what we thought was the right thing in very complex situations and under extreme duress.

There is sort of a coin toss at the beginning of the war. The winner gets to choose between 400,000 additional warriors on their side, or Krishna on their side – and Krishna cannot fight. He can only advise.

Arjuna wins the coin toss, and he chooses the advice of Krishna. The Kauravas get the 400,000 warriors.

The armies have lined up. And the story takes place in that moment of quiet, prior to the insanity striking.

Any soldier or first responder knows this uncomfortable calm. Everyone is bracing for the violence. In this moment, we collect our wits, and mentally prepare for the possibility of not surviving the situation.

Arjuna and Krishna pull their chariot out into the space between the two armies. They survey the massive army of The Kauravas, and the small army of The Pandavas.

Arjuna sees, in the opposing army, his friends, family members, teachers, lovers, neighbors, and he sinks into doubt.

“I can’t do this – why should I fight?” he asks Krishna.

And the rest of the story is all about why Arjuna must fight, why it is right, why not fighting would be violating his karma, and how yoga can prepare him to understand why he must fight:

“It’s your karma – your duty, your destiny. If you fulfill your destiny, then, whether you live or die, you have done what is right. If you refuse to fight, you have denied this.”

A lot of The Bhagavad Gita has to do with devotion and sacrifice. Krishna says a lot of things about being devoted to him, making sacrifices to him, and so on, that seem like real turn-offs, seem like ego, and push a lot of westerners away from this book and philosophy. However, it dawned on me, recently, what this might really mean:

The same way Jesus said ‘drink from my mouth,’ the metaphor is kind of gross, and it makes us think that Jesus is speaking from his own ego. But, if we look at the egolessness, and see Jesus as a conduit for divine teachings, then it becomes more accessible. Similarly, Krishna cannot be concerned with himself, and the book even refers to him as ‘the egoless one.’

Remember, too, that your trauma probably stemmed from an egoless situation. One in which you put your thoughts of yourself and your safety aside for the benefit of someone else.

I think Krishna really means the spark of life we all carry inside of us. We all, instantly, know the difference between a living and a dead thing, and even between a healthy and unhealthy thing. There is something that just sees it and knows it.

In fact, the yoga (Sanskrit) phrase Namaste refers to knowing this spark or flame inside of someone else, since we know it in ourselves.

We see it in all of us, and that is what motivates people like first responders, soldiers, teachers, heroes, and all people who serve.

I recently came across a house that had started on fire. The police had just arrived, and I watched them breaking the windows to the house and going in.

This seems to defy everything we are made of. Most people try to get out of a fire, but, thank God, we have a class of people who run into fires and save people.

Why do they do this? Why do they put their lives at risk, for $40,000 a year, our whatever, day after day? Why do they risk everything to help someone they don’t even know?

It is because they know the value of life. They know it in them, and they know it in others, and they recognize that that spark or flame of life is exactly the same. So, it is really like they are saving themselves. And, if you ever see a first responder who was unable to save someone, it is almost as if they couldn’t save their children, or themselves. The disappointment is that great.

Therein is devotion – recognizing and responding to the life inside another person. And there is sacrifice – the willingness to give oneself to help another.

I think that understanding that a lot of people who have trauma histories, or PTSD, can relate to this, and it helps others understand why someone would willingly give themselves for another, when most people run away.

In the case I saw, I read, later, that the police saved a disabled man from the house. The officers I saw were in the hospital for smoke inhalation. They could have died, easily. That didn’t stop them from carrying out their duty.

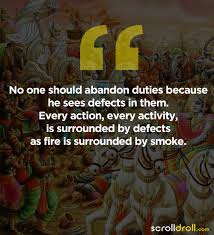

The Bhagavad Gita makes several other important points:

- As we mentioned, service, to a lot of people, is a duty and a calling seemingly given at birth. There is a Hindu caste system, which, unfortunately, has been more used as a form of abuse, but it is based on this idea that people are born for particular purposes, and the warrior class is one of them. I worked with some Marines at The American Embassy in Moscow. We all had to wear hard hats in a construction zone. The Marines decorated theirs with slogans like ‘born to die.’ This is not a sentiment that is shared by many, but, to a warrior, it really is a true thing – and one can see that outside of the realm of being a warrior, this is a difficult sentiment to have. We have an epidemic of suicides, homelessness and mental illness among our service people that, I think, comes from bringing this ‘born to die’ attitude into the mundane living of everyday life.

- The Bhagavad Gita specifically addresses good and evil, and talks about the duty of good people to stop evil people. A lot of yogis even go to the point of trying to say that good and evil don’t really exist – that there aren’t bad people, only confused people. The Bhagavad Gita leaves no doubt that there are inherently evil people who harm others, and that the warrior class has the duty to stop them.

- Krishna uses the opportunity between the two armies to paint a very expansive picture of yoga and the universe. At one point, Arjuna asks to see who/what Krishna really is, and Krishna then takes on a form of showing millions of past and future lives, all the starts and galaxies of the universe, and the great expanses between the two. This, I feel, parallels the psychological explanation and treatments for PTSD:

In yoga, there is a theory of ‘samskaras’ – these are habituated patterns of thought and behavior that we all have. There are good samskaras, like being kind and brushing your teeth, and there are negative samskaras, like when we get stuck making the same mistakes over and over and over and over. They are like worn ruts in erosion. A good ditch can take the water away from things it might hurt. But other patterns of erosion get deeper and deeper through more use, and these can wipe out yards, damage houses, Destroy driveways, and so on.

We know that trauma changes our brain chemistry. We know that in ‘fight and flight’ we develop very primal patterns that help us stay alive.

We know that ‘flashbacks’ – the re-experiencing of the trauma, happen when a stimulus, like hearing a firework, triggers that part of the brain that has a pattern worn in it during a time someone was shooting at us. And, in and instant, we can forget that we are in the comfort of our homes with our families, and we can be back on the street where the shooting happened – hearing the sounds, smelling the smells, our hearts pounding and breath shortening as we re-experience trying to find cover. The neural synapses that fired then start firing again. And we are stuck in sort of a ‘short loop’ – the situation just playing over and over. And, even if we can tell ourselves we are safe with our families, and no one is shooting, the reptilian part of our mind doesn’t believe it.

The solution, through self-work, EMDR, meditation, therapy, medication, whatever, is to reconnect with our more powerful, well developed rational mind.

A metaphor of salt in a cup helps clarify- in a cup, a spoon full of salt spoils the water – makes it too salty to drink. This is what the flashback is like. But, if we can pour the salt water into a pond, the pond is so full of fresh water that the salt can’t even be tasted, even of we know it’s there.

Being able to connect these memories and the activation of them in our ‘fight and flight’ parts of our brain to put them in context with the rest of our lives and the present moment can help these memories move from being haunting phantoms to being memories.

Obviously, the more these patterns get worn, the longer period of time we run them, and the depth of the ruts they make impact how difficult it is to connect to the rest of our lives and dilute the memories.

It really is, like Krishna points out, if the whole of our world is these memories, then that is very difficult. If we can remember we are parts of bigger things – parts of groups of friends and families – part of a society – citizens of a country – surrounded by hundreds, thousands, millions of people, all with joy and trauma – part of living on this earth – inside our vast galaxy, and so on… The bigger the universe gets, the more the trauma can come into perspective.

A lot of times peoples’ trauma is made up of really a limited number of minutes or hours or days inside a huge, vast, wonderful creative life and world. This is impossible to remember when we are stuck in the trauma or in the post-traumatic stress, but it is true. And the more we can connect with the purpose of what we did and what we do, the more we can connect with the truth of the expansiveness of life, the better we can function.

We are not much help if we are stuck inside ourselves and stuck inside our trauma within ourselves.

One of the yogas Krishna talks about is ‘karma yoga’ or service and ‘kriya yoga’ or the yoga of action. By serving in a non-traumatizing way, and by participating in action – getting out, talking to people, exercising, and so on, we can reduce the impact of trauma in the moment.

Ram Dass is a western yoga teacher who went to an ashram in India and met a guru in the 1960s. At one point, after becoming enamored with his guru, and wanting to experience more of what his guru, Maharajji, was experiencing, he asked his guru ‘How can I know God better?’

Maharajji answered ‘Love people and feed people.’

And maybe this is a way we can help with trauma, too.

Chances are, if you experience trauma and suffer as a result, you didn’t do anything or very much wrong that created the trauma. For lots of people, it was when you were trying to help others, and save others. For some, it is that you were hurt by an abuser.

In my experience, one of the hardest things to deal with in regard to the trauma, is the guilt I feel about having trauma. I feel so bad that I have to stop, and struggle to take care of others, and I feel weak and vulnerable and angry that I have PTSD. I feel like I am letting people down by not being as strong, in the moment I am struggling, as I was when I was helping people in a pretty super-human way.

Surprisingly, none of this is helpful, but it is very common. Part of the getting stuck inside the samskara. Especially abuse victims feel guilty about being abused. That sounds do strange when it is said out loud, but you didn’t do it. The abuser did. Get someone to tell you, and tell yourself you do not need to be ashamed for being hurt.

It’s OK to not want to fight, for an instant. But you did, you did what you needed to do. It left scars. It hurts. It is part of you.

Use this as your medicine. You survived something a lot of people couldn’t have. You did something most people won’t do. Warriors are a special class. Our society is horrible about recognizing and honoring warriors. We shame them. They end up on the streets and worst. When soldiers came back from Vietnam, having, heroically, done what they thought was the right thing in the moment – what generals and presidents and entertainers told them what was right – and then they came back to being called ‘baby killers,’ I can’t imagine how this felt hurtful and confusing. And, even today, for people coming back from Iraq or Afghanistan to be denied care at the VA, and sent out to find a job in an office after fighting enemy combatants in a strange land. Or first responders from 9/11 being made to walk in parades, and used by politicians as subjects of their speeches about patriotism, and then to be denied medical assistance, reparations for their heroism, and to be left alone must be devastating. Being yelled at to be responsible and go get a job, and stop being a parasite after keeping people, countries, our values safe and sacred must feel worse than dying would have.

One of the primary forms of torture is to convince someone they are going to die, and then they don’t die. Most people who have experienced trauma have lived this. You have survived torture.

It is time for us to honor our warriors. It can start small – with yourself, and spread.

Make your trauma into the medicine that propels you forward, not into shame. Being a warrior is magical. It is a gift. It is something no one but other warriors can understand, because we experienced it and survived it. Own it. Be it. Carry the pride, even though our world tries to cut us down for not being ‘normal.’

We answered a calling and did our duty. That is what honor is.

Our trauma is like an abrasive that has shaped us into who we are. A samskara can be a muddy ditch, but, over time, the muddy ditch can become a grand and mystical treasure like The Grand Canyon. If we think of trauma as a polishing rather than as a wearing down, maybe it is a better metaphor.

Let your trauma be a point of pride, rather than an injury.